The Serviceberry Mindset: How Nature’s Gift Economy Can Reshape Data Governance

For years, we’ve heard that breaking down data silos is the holy grail of business transformation. We’ve been told that better pipelines, integrated analytics, and AI-driven decision-making will finally unlock the full potential of enterprise data. But here’s the question no one seems to ask: What if we’re still thinking too small?

The real challenge isn’t just technological—it’s conceptual. We don’t just need better data governance or cleaner metadata. We need a way of thinking that moves beyond technical optimization and into deeper creative problem-solving. That’s where multidisciplinary thinking comes in.

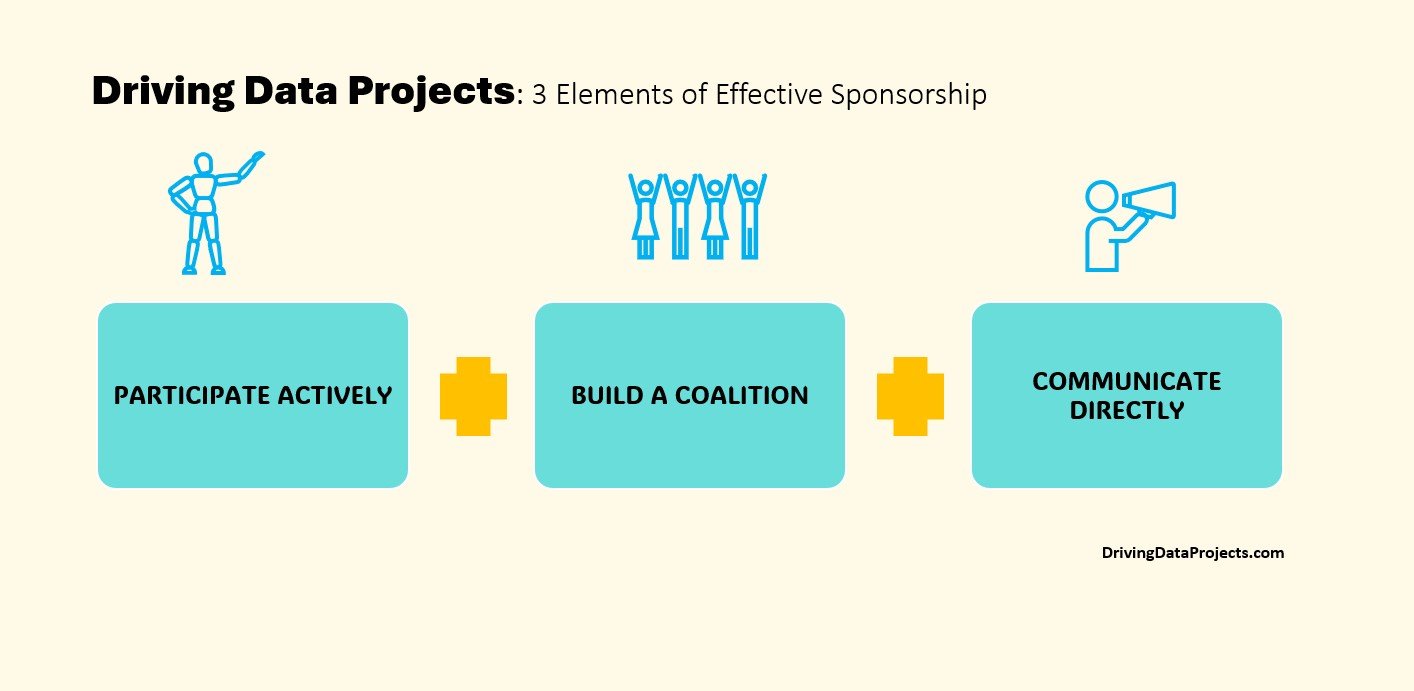

3 elements of effective sponsorship

A popular misconception of senior leadership is that effective executive sponsorship is a clearly understood skill. Many assume executives receive developmental feedback about becoming effective sponsors. Sadly, there is little training on sponsorship from middle management on up.

Leaders often accept sponsorship of an activity, not knowing what it entails. Some think it means sending a few enthusiastic emails about an initiative, propping up delegates in meetings, and moving on to the next thing. Some organizational cultures tolerate those actions as enough.

The Pandemic Highlights Humility In Short Supply

If knowledge, expertise, and training do not protect against overconfidence, what does? There is one thing that everyone can do. Research advises us to embrace empathy and understanding. Consider the reasons that you may be wrong. Reducing overconfidence in yourself or others, requires us to ask: How are we mistaken? What conditions might my conclusions be incorrect? These questions are hard because we generally enter discussions attempting to prove we are right. Engaging in thinking exercises that we might fail brings up our vulnerabilities. Being vulnerable reduces our overconfidence and increases our sense of humility with our expertise.