AI, Adaptability, and the Stories We Tell Ourselves

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly changing how we work, make decisions, and define success. But when AI or any new technology suggests something unexpected, how do you react? The answer is shaped more by your experiences than the technology itself and more to do with your Data Biography — the sum of your experiences, reactions, and assumptions about data that shape how you engage with new innovations. By understanding your data biography, you can improve your adaptability, enhance decision-making, and ensure you control new technologies — rather than letting them control you.

Sitting in the Fire, With Maria

Global leaders deal with chaotic and changing situations, often filled with tension and conflict, which can make people feel excluded and prevent #community building. Two disparate yet connected fields grapple with the continued emergence of ethical dilemmas: #Technology and #AI, and #DEI. As much as we think these fields aren’t related, how we manage #conflict, check our assumptions, and navigate connection is what creates the path forward.

The Great Wave

Hokusai's story exemplifies many of the key themes im exploring in a current manuscript about the importance of subjective intelligence in the advent of ai: the importance of #persistence, the value of #lifelonglearning, and the deep #insights that can come from looking closely at one's craft over an extended period.

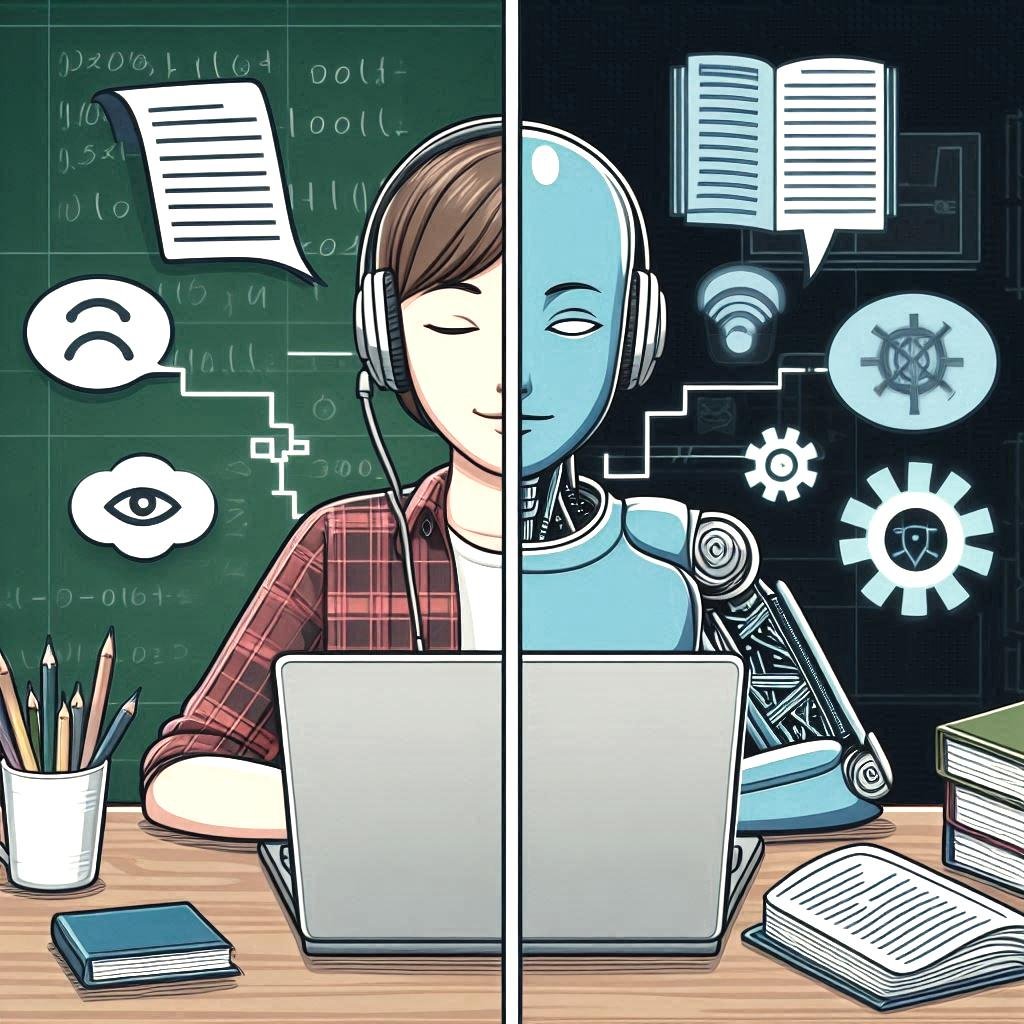

The Double-Edged Sword of AI in Education and Work: Lessons from the Frontlines

As adjunct faculty, I get a front-row seat to the AI revolution in education and the workplace. What I've observed is both exciting and concerning, a paradox that we must navigate carefully as think about our future work.

How real is Singularity? #KnowYourJargon

Singularity, the idea that technology will surpass human intelligence, is an irrelevant red herring in our current world. In becoming preoccupied with this debate, we miss numerous nearer-term milestones relating to synthetic media or misinformation being met with growing frequency and instead contemplate esoteric questions about consciousness and sentience.

Transparency and Explainability Don't Equal Trust

Trust is transitioning from institutional to "distributed," shifting authority from leaders to peers, which is often overlooked and perpetuates trust issues. If trust is predictable, it isn’t needed – is it? If the inner workings of AI, government, and the media were just more transparent, if we knew how they worked, we think we wouldn’t really need to “trust” so much. It would be more predictable.

Taxonomy v Folksonomy

The concepts of taxonomy and folksonomy hold significant implications, especially in the context of emerging technologies like OpenAI. While traditional taxonomies offer structured hierarchies of knowledge, allowing for a systematic approach to information organization, folksonomies represent a more fluid and emergent way of categorizing information based on user-generated tags and metadata.

However, the challenge arises when technological advancements fail to incorporate divergent thinking and promote groupthink through convergent taxonomies. This phenomenon is particularly evident in language models, where developers' linguistic and cultural biases can influence the interpretation and representation of (the dominant) language.

Who is pacing this race?

Employees have been encouraged to ‘automate their roles’ to demonstrate self-direction and continuous learning. In the past, an employee's skills, motivation, and business interests determined the pace of change. Soon, the pace may be beyond their control, risking job loss before they can adapt to consider the next set of problems. If they can’t find problems faster than the pace of automation, they are not adequately prepared for transition.