Whatever the topic, I have to remember that the first thought is not my fault. First thoughts are always a reaction. From bird flocks to fish schools to herd animals, we often seem to react to being perturbed as if of one mind. Flocks behave as critical systems, poised to respond maximally to being perturbed. And that makes sense. It’s about coping to survive. I can relate to that. My initial thought is followed by assumptions and later firmer beliefs that are designed to protect me–and they do, for a time. All that mental motion builds momentum, like a flock of birds acting as if one mind.

But I need to own those later thoughts. The assumptions and beliefs that follow form my world view–and I want my worldview to be flexible. Somewhere, in that pack of starlings, is an essence of me that gets lost.

My work in the world is to help people process their sources of conflict in order to become more effective personally and professionally–to help them feel what they feel and know what they know. At the end of the day, that’s what it comes down to.

So it doesn’t matter what I’m doing throughout my day, whether I’m sleeping, eating, walking, or thinking–I can maintain my goal of providing strategies for relief. As part of that dynamic, I take on a bit of their misery. Providing empathy means I feel into their experience by literally experiencing the feelings of the other person. To maintain my slogan of alleviating suffering by taking on misery, I have to remember my motivation.

For instance, I should not eat merely to satisfy hunger. If I’m living my slogan I eat in order to maintain strength, prolong my life, and thereby be able to fulfill my aspiration of benefiting others.

Looking at the daily task of eating, sleeping, thinking, and working in this way makes every act I engage in bigger. It’s no longer just about “me and my hunger,” or “me and my needs” whatever they are. My mission in life starts to frame my experience.

My daily activities can be more worthwhile if I approach them with a similar motivation. It is hard to adopt this broader view of life all the time. That is why it’s a practice. It takes a lifetime to achieve. And if I’m honest, I’ll probably die trying in the pursuit.

But it does give me a sense of joy and even a little excitement to think that my smallest acts are somehow benefitting someone else energetically. It’s proof, at the most fundamental level, that we are all truly connected. We matter, whether we like it or note. And it is important for me to remember that how I talk to myself today, how I treat myself today, impacts the people I meet next week.

Taking the time to think of my life or the potential for my life this way saves me from succumbing to busy work. Knowing what I’m about provides a tremendous source of comfort when I’m told by someone else that I’m not good enough as I am.

In taking the time to identify a thought and see it through, I benefitted. How often do we really do consider an idea and think it through to its conclusion? I found it calming and it gave me a sense of direction to the choices I have to make.

So yes, I use slogans to advance my learning. But to come up with one, I needed to understand my motivation for it. It is hard work because I tie it to my Craft and try to hold myself accountable to it.

Fewer slogans, greater accountability.

What is your slogan?

The anvils dated back as far as the 1700s - if they could speak I'll bet they'd have some stories.

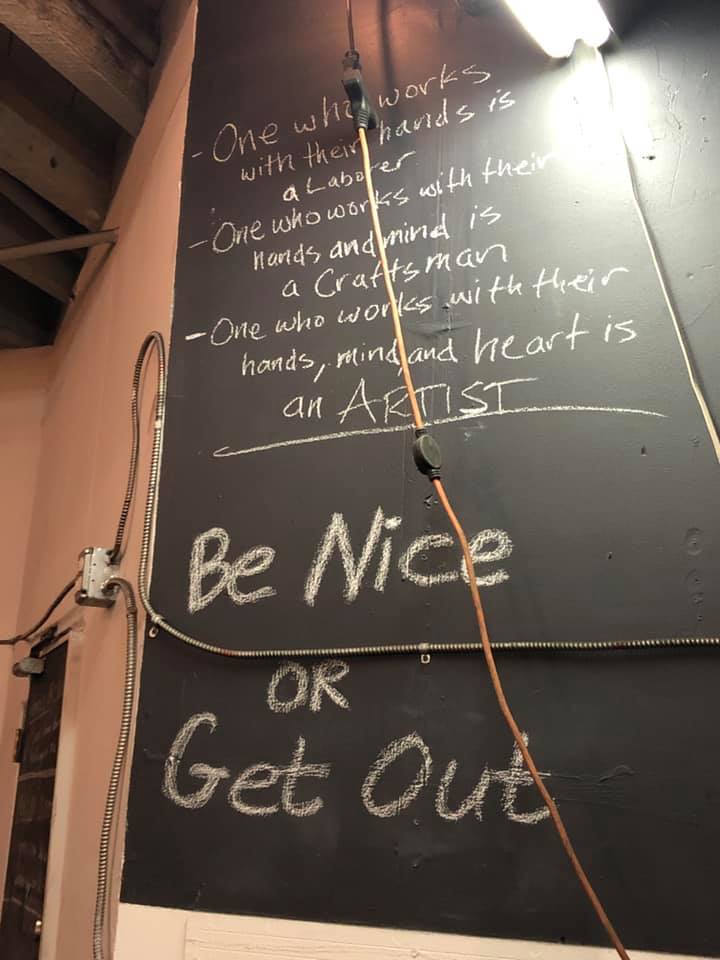

The anvils dated back as far as the 1700s - if they could speak I'll bet they'd have some stories. There was an ethos.

There was an ethos. We came in with a simple understanding of what we might be making: garden sticks of some kind.The instructor came to my friend and I and asked, "What do you want to make?" We thought the experience was pre-defined for our success. We did not expect to have to have invested in a vision--and for the most part it was. But the open-ended question was instantly intimidating. But with freedom came inspiration.Pinterest would guide us. Yes, that is where all good ideas come from, isn't it?"How about this?" No.

We came in with a simple understanding of what we might be making: garden sticks of some kind.The instructor came to my friend and I and asked, "What do you want to make?" We thought the experience was pre-defined for our success. We did not expect to have to have invested in a vision--and for the most part it was. But the open-ended question was instantly intimidating. But with freedom came inspiration.Pinterest would guide us. Yes, that is where all good ideas come from, isn't it?"How about this?" No. "This?" Too complicated.

"This?" Too complicated. "What about--" No.

"What about--" No. Left to our own devices, we had high hopes and big dreams.

Left to our own devices, we had high hopes and big dreams. And, we met reality.

And, we met reality. Comments from the time we spent give you some sense of the arc of our experience:

Comments from the time we spent give you some sense of the arc of our experience: