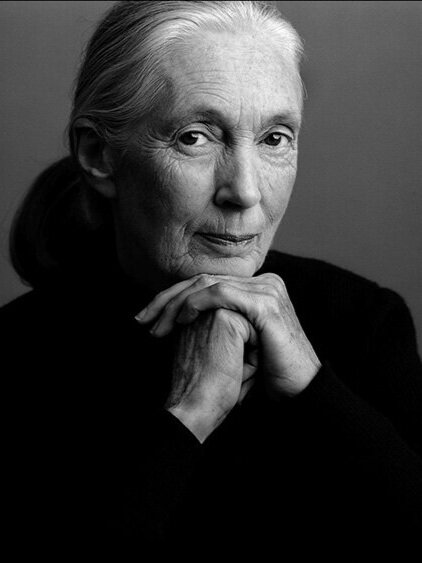

Profiles in Craft: Jane Goodall

CURIOSITY 101

Image Credit: Jane Goodall Institute

Jane Goodall (1934—) is an English primatologist and anthropologist. Considered to be the world's foremost expert on chimpanzees, Goodall is best known for her 60-year study of social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees since she first went to Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania in 1960, where she witnessed human-like behaviors amongst chimpanzees, including armed conflict.

The debate of what distinguishes us from animals is an old one, but only recently have animals gone from objects to be observed to fellow beings to be understood, with their own complex psychoemotional constitution. Hardly anyone has contributed more to this landmark shift in attitudes — or, rather, this homecoming to the true nature of things — than Jane Goodall. She has dedicated her career to fusing scientific rigor of primatology with the spiritual wisdom of a philosopher and peace advocate.

In this wonderful short video from NOVA’s series The Secret Life of Scientists and Engineers, Dr. Goodall considers how empathy for other animals brings us closer to our highest human potentiality.

CURIOSITY 101

Curiosity starts with empathy. Bring curiosity wherever we go to increase possibilities for connection and creativity.

Curiosity starts with empathy. Our brains scan for threats and rewards 5 times a second. Maintaining multiple levels of awareness while our brains scan the environment is a lot to keep track of—and, we also have to bring people along with us. We want people to be leaning in and feeling that working with us is a place of safety, not one of risk. We also understand that we want feelings of safety for ourselves, too. When we make ourselves feel safe first, we are doing our best work.

So how do we cultivate our own curiosity while we are contending with status quo, pressure, or threat?

How we show up influences the environment that drives engagement. We have four primary drivers that determine how we read any given situation, listed below with common questions that might be swirling in our minds.

They are summarized here as our "C-Index":

Community. Are you with me or against me? If we are seen as being part of the team, we will be safe. If we are seen as an outsider, we risk being shunned, left out of important decisions, or somehow cut off.

Certainty. Do I know the future or don’t I? If we know the next step, we feel safe. If the path is unclear, we feel less safe.

Control. Are you more or less important than me? If the person we are talking to does not recognize our role or boundaries, we will feel less safe.

Choice. Do I get a say? Our level of autonomy is critical in gauging our level of reward. The less choice we have the less safe we feel. “The ultimate freedom of creative groups is the freedom to experiment with new ideas. Some skeptics insist that innovation is expensive. In the long run, innovation is cheap. Mediocrity is expensive—and autonomy can be the antidote.” –Tom Kelley, General Manager, IDEO

Curiosity can happen in every conversation. For it to appear, we have to remove our assumptions, judgments, and beliefs about how things have been in the past. Our goal is to increase our C-Index wherever we go.

How do we stay curious in our day-to-day, when we don’t feel safe, are under pressure, or perceived threat?

PRACTICE

Curiosity isn’t about winning Nobel prizes, though that is certainly a potential outcome. It’s about seeing possibilities in every interaction.

Remember that when working with other people, you are also working with their triggers in addition to your own. For instance, when others hear about bits and pieces of a strategic plan from peers rather than from us, it might bring up the feeling of being left out (i.e., not having a say). While we don’t intend to show up as threatening in any way, some actions might inadvertently have an impact.

Identify an interaction you had with someone that could have gotten better than it did. There might have been a misunderstanding, or snag of some kind.

Tend to yourself, first. Determine your own C-Index for that moment. How do you answer the C-Index questions, for yourself, at that moment? Once you know what came up for you, you can start to tend the other and repair the situation.

Then, consider how the person you were speaking with might have responded to those questions. You are not asking them directly, you are perceiving how they might respond given what you know. Might they feel left out by what occurred, or did they have a say?

Sample Scenario:

Two people are in conversation. Donna gave Mary feedback on a project. Mary nodded and tried to add a clarifying point, but Donna cut her off, labeling Mary as “defensive.”

Donna scans herself, first, with honesty.

“Why did I think Mary was defensive?” What was I feeling at that moment?

“Mary had a big accomplishment; she completed a project that had taken a long time and a lot of effort. But, it didn’t speak to me personally. In fact, I discounted it. I see other trends in the marketplace and wanted to share that with her. I think I was embracing “certainty” at that moment. I was certain about my experience and my observations of the marketplace—and I think that is what came across. I didn’t lead with much if any acknowledgment of her work, I didn’t even dig into her project to really understand what she was doing.”

Donna perceives Mary’s C-Index

“I said her project wasn’t relevant, and that was clumsy of me. I could have delivered my feedback in a more skillful manner. When Mary tried to clarify something, I immediately judged her as defensive, which probably made her feel defensive. She was only trying to give me some context because I wasn’t intimate with the details of her project. She might be thinking that I’m “against her.” I might have tripped her “community” wire.”

With this new perspective, Donna can slow the conversation down, see her potential impact in the dynamic, communicate what she meant to say in a more effective way, and check-in with Mary to see how her comments landed.

COMMIT

[ ] I commit empathizing with others’ experiences to increase my curiosity about the possibilities of a “third story.”

FURTHER READING/ WATCHING

In the Shadow of Man: Steven Jay Gould called this book “one of the Western world’s great scientific achievements” and a vivid, essential journey of discovery for each new generation of readers. This account of Jan'e’s life among the wild chimpanzees of Gombe is one of the most compelling stories of animal behavior ever written. For months the project seemed hopeless; out in the forest from dawn until dark, she had but fleeting glimpses of frightened animals. But gradually she won their trust and was able to record previously unknown behavior, such as the use—and even the making— of tools, until then believed to be an exclusive skill of man. As she came to know the chimps as individuals, she began to understand their complicated social hierarchy and observed many extraordinary behaviors, which have forever changed our understanding of the profound connection between humans and chimpanzees.

Reason for Hope: Goodall’s work forever altered the very, definition of humanity. Now, in a poignant and insightful memoir, Jane explores her extraordinary life and personal spiritual odyssey, with observations as profound as the knowledge she has brought back from the forest.

What separates us from chimpanzees? | Jane Goodall (Ted Talk) Jane Goodall hasn't found the missing link, but she's come closer than nearly anyone else. The primatologist says the only real difference between humans and chimps is our sophisticated language. She urges us to start using it to change the world.

In Her Words…

“What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

“The greatest danger to our future is apathy.”

“In what terms should we think of these beings, nonhuman yet possessing so very many human-like characteristics? How should we treat them? Surely we should treat them with the same consideration and kindness as we show to other humans; and as we recognize human rights, so too should we recognize the rights of the great apes? Yes.”

“You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

“We have the choice to use the gift of our life to make the world a better place--or not to bother.”

“Only if we understand, can we care. Only if we care, we will help. Only if we help, we shall be saved.”

“Change happens by listening and then starting a dialogue with the people who are doing something you don't believe is right.”

“We have so far to go to realize our human potential for compassion, altruism, and love.”

“Every individual matters. Every individual has a role to play. Every individual makes a difference.”

“Each one of us matters, has a role to play, and makes a difference. Each one of us must take responsibility for our own lives, and above all, show respect and love for living things around us, especially each other.”—Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey

“Lasting change is a series of compromises. And compromise is all right, as long your values don't change.”

“It is these undeniable qualities of human love and compassion and self-sacrifice that give me hope for the future. We are, indeed, often cruel and evil. Nobody can deny this. We gang up on each one another, we torture each other, with words as well as deeds, we fight, we kill. But we are also capable of the most noble, generous, and heroic behavior.”— Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey

“...it honestly didn't matter how we humans got to be the way we are, whether evolution or special creation was responsible. What mattered and mattered desperately was our future development. Were we going to go on destroying God's creation, fighting each other, hurting the other creatures of the His planet?”

What we don’t see on the resumes we review or the job descriptions we want is the litany of emotional entanglements we bring to our roles, uninvited, to the team and organizations we work in. Alongside technical skills, people who can master a range of subjective skills are better able to influence, deal with ambiguity, bounce back from setbacks, think creatively, and manage themselves in the presence of setbacks. In short, those who learn lead.

Observing subjective qualities in others past and present gives us a mental picture for the behaviors we want to practice. Each figure illustrates a quality researched from The Look to Craftsmen Project. When practiced as part of our day-to-day, these qualities will help us develop our mastery in our lives and work.

References:

Renner, B. (2006). Curiosity about people: The development of a social curiosity measure in adults. Journal or Personality Assessment, 87(3), 305-316.

Kashdan, T. B., Rose, P. & Fincham, F. D. (2004). Curiosity and exploration: Facilitating positive subjective experiences and personal growth opportunities. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82, 291–305.

Kashdan, T. B., DeWall, C. N., Pond, R. S., Silvia, P. J., Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D.,… Keller, P. S. (2013). Curiosity protects against interpersonal aggression: Cross‐sectional, daily process, and behavioral evidence. Journal of Personality, 81(1), 87-102.