Robert Tinney: A Piece of Public Imagination Vanishes

Byte magazine artist Robert Tinney, who illustrated the birth of PCs, dies at 78. The significance of this obituary isn’t just “a beloved illustrator died.” It’s that a major piece of the public imagination of early personal computing has just formally passed into history. Tinney helped invent the visual language of personal computing.

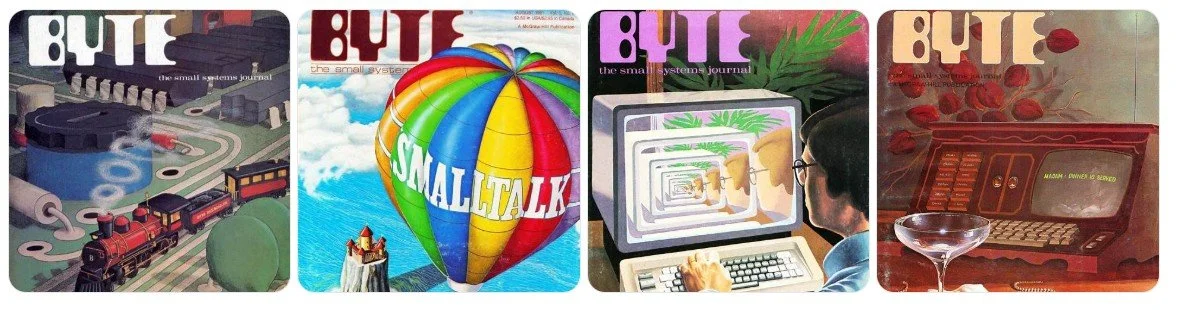

In the late 1970s and 1980s, “microcomputing” was still abstract to most people: invisible processes, weird jargon, uncertain stakes. With each cover for Byte, he turned concepts like networking, programming, and eventually “AI” into instantly graspable metaphors—surreal, playful, slightly uncanny, and memorable.

That matters because metaphors become defaults. Once a community shares a set of images, it becomes a shared way of thinking.

His outsider status was the feature, not the bug. Tinney didn’t identify as a “computer person,” and that’s precisely why the covers worked. They weren’t insider diagrams; they were translation artifacts for curious amateurs, hobbyists, and future professionals. In other words, he visualized computing before computing had settled into today’s corporate self-seriousness.

He shaped icons that outlived the magazine, especially Smalltalk. The obituary nods to the August 1981 Smalltalk cover (the balloon). That image wasn’t just pretty; it became a cultural symbol in programming lore, preserved as a commemorative print in the Computer History Museum collection. The balloon story is directly tied to the Smalltalk community’s historical narrative (including recollections by Dan Ingalls).

Before most people could touch computing, they had to mentally model it, and Tinney’s covers functioned like early “UX” for the public imagination, translating specialist ideas into shareable metaphors. Robert Tinney supplied the metaphors: not diagrams, but sensemaking. His covers served as an interpretive bridge between specialists and curious outsiders, exactly the boundary where adoption, investment, and cultural confidence are made.

Image Source: Lunduke Substak

Tinney wasn’t just an illustrator for a tech magazine; he helped brand a paradigm through shared imagery…a time period, like a capsule. He captures the moment “computing” stopped being a frontier and became a product shelf. One of the most telling details: Byte eventually moved from commissioned illustration to product photography as competition intensified. That’s not just an art-director choice; it’s a signal of commodification—a shift from “imagine what this could be” to “here’s the box you should buy.”

Still Relevant Today

Tinney’s career arc mirrors the industry arc: wonder → market → optimization. He later reflected on how stock image databases changed the economics of illustration. Sounds a bit like a prequel to our current moment: abundant images, thinner meaning, collapsing pay for craft.

If early computing needed humans to translate the invisible into shared metaphor, what happens in an AI-saturated era where images are cheap, but coherent, trustworthy metaphors are not?

Tinney mattered because he helped a generation see personal computing before it was fully understood. He was an early meaning-maker for the PC era, not just a decorator, reminding us that how we picture a system gradually shapes what we permit it to become. (RIP, Tinney)