Christine Haskell, PhD, is a different kind of technology advisor.

She focuses attention on keeping values in the room.

Her work spans adaptive leadership, data protection, artificial intelligence, and relational governance.

Christine Haskell guides a reflective leadership training program and is a trusted advisor to leaders where data, systems, and values intersect.

Pencils to Pixels Press, 2024

British Computer Society, 2024

Wiley, 2025

A seasoned educator and researcher, Christine helps leaders slow down, think clearly, and act with integrity—especially under pressure. Her work bridges the human and technical sides of leadership, offering clarity where complexity has taken root.

“Governance isn’t about making the right decisions.

It’s about making decisions right. And that begins with reflection.

Programs

lead from within

Rolling 4-week cohort (20 max)

Navigate complexity and lead through values-based tension.

lead with insight

Rolling 4-week cohort (20 max)

Build alignment across teams, governance, and implementation.

AI without the hype

Understand AI’s impact on work—before momentum decides for you. (2 Hours)

Upcoming Trainings

-

Lead From Within

3.16-3.18 (Virtual)

Learn to lead through ambiguity, resistance, and pressure—by recognizing and shifting your own patterns.

-

Lead From Within

3.30-3.31 (Virtual)

Learn to lead through ambiguity, resistance, and pressure—by recognizing and shifting your own patterns.

-

Lead With Insight

4.2-4.3 (Virtual)

Strategic training for leaders facing friction between transformation goals and on-the-ground capacity. When the plan looks good on paper, but nothing’s changing.

Hear What People Are Saying…

★★★★★

Suzanne C.

Christine Haskell isn’t like other speakers. She guides participants to unpack [complex] concepts in new ways… and has transformed my understanding of deep listening, especially in tension-filled moments. Through skillful demonstration and facilitating hands-on practice, she and her co-presenter modelled how to lean into conflict boldly, but with grace. Christine presented practical tools that I've carried forward in both professional and personal contexts and integrated into my teaching.

★★★★★

Ashleigh K.

Christine engages the class. I enjoyed the group work and appreciate the perspective she brings. Her exercises were very helpful, and her stories flow well, making concepts easy to apply. I would love a couple more sessions with her!

★★★★★

Bill R.

Christine is the real deal. I like her many personal examples. She provides a very detailed workbook, which is helpful. There are a lot of good nuggets, even for someone like me who has been around a while.

★★★★★

Melissa R.

My lack of experience challenged me, but Christine helped me discuss concepts and build my confidence. We had excellent discussions that I can bring back to my organization. I feel like I can actually go back and do something. I can’t wait to get back and get started!

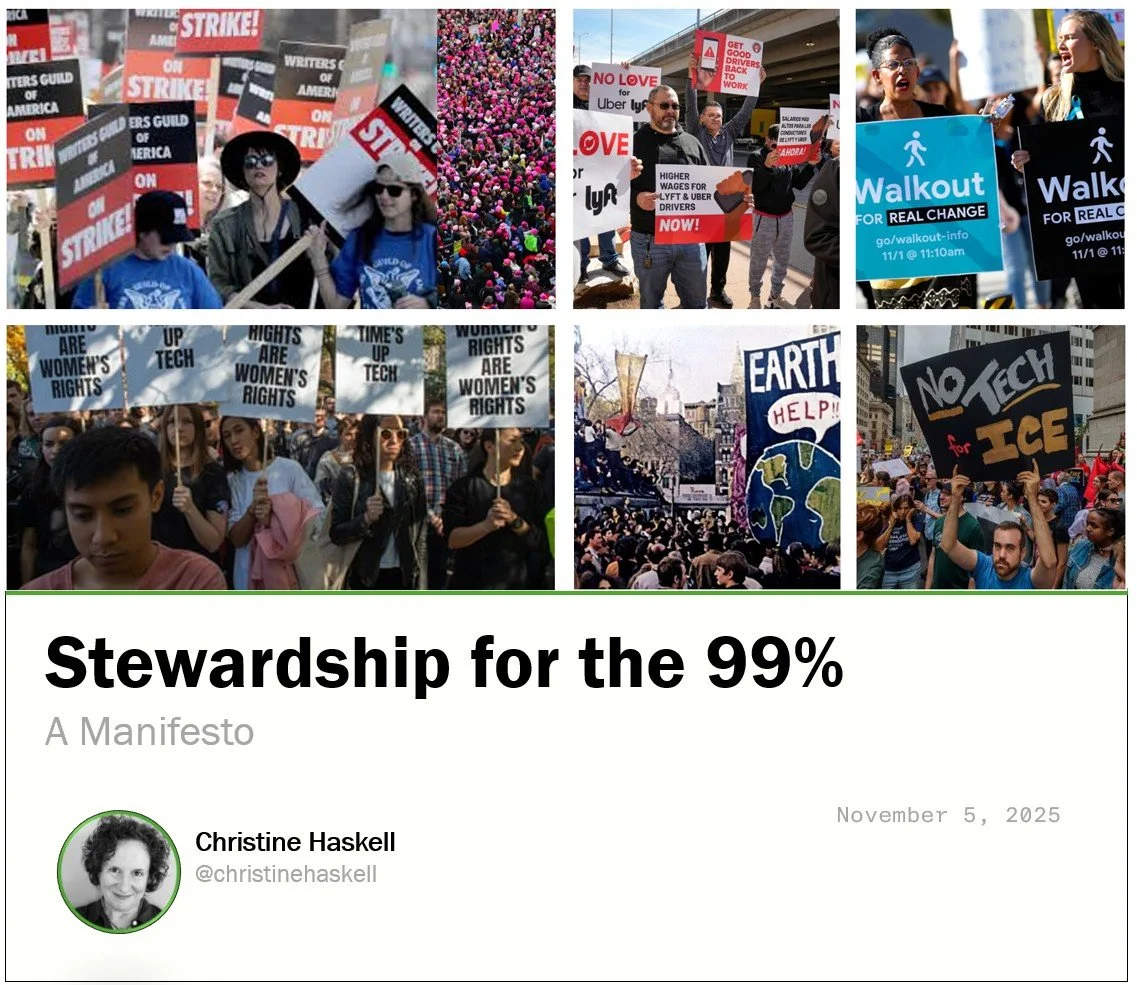

Christine Haskell, Ph.D., is a scholar-practitioner working at the intersection of AI, data governance, and leadership, with a focus on stewardship—the practical work of setting jurisdiction, accountability, and limits before technology scales.

Her manifesto anchors this work, advancing a governance-first approach that helps practitioners, educators, and decision-makers challenge inevitability narratives, surface power dynamics, and reclaim human authority over systems that shape real lives.